Faculty Spotlight: Benjamin Neuman

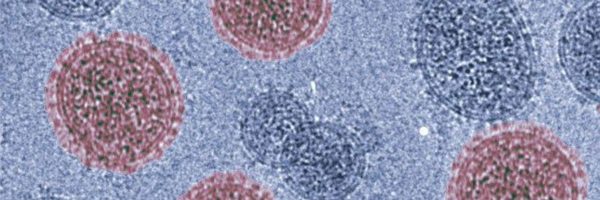

Benjamin Neuman was born to parents Doug Neuman and Billie Porter Neuman in Niles, Ohio. As the oldest of four children, he attended Niles McKinley High School before enrolling at the University of Toledo for his bachelor’s degree. Following this, he enrolled at the University of Reading for his PhD in Animal and Microbial Sciences and completed his postdoctoral research in virology at the Scripps Research Institute. Dr. Neuman joined the faculty at Texas A&M Biology in 2021. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Neuman served on the international committee on the taxonomy of viruses, a COVID-19 study group. He oversaw the Texas A&M University Global Health Research Complex which identified a variant of the virus whose full significance was unknown.

What is the best advice you’ve been given?

What is the best advice you’ve been given?

In practical terms, “always have something to present at the lab meeting” was a good one – a challenge to keep your feet moving, so to speak, even if it seems like you are stuck. A technician told me that during a tough time in my PhD, and it really helped. The other advice I like is that when opportunity knocks, say yes and find a way. I know it sounds ridiculous to say, but “be an Alessandra Ambrosio” has been a guiding principle in talking to the media. Back when the Victoria’s Secret catalog was a thing, the really big names would all have a picture or two in the front. But the entire rest of the book was Alessandra, page after page. I have no idea how it came about, but I assume someone asked, and she said yes and got to work. It’s not always glamorous, but somebody has to fill the void, whether it is the rest of the catalog or the news cycle, and better it is done by someone with a level head and a bit of expertise. That’s the goal, anyway.

What is on your bookshelf?

All the Murakami and Bukowski I could find. Murakami, as a friend put it, has a wonderful way of going straight over the edge into the surreal. “The Strange Library” is a good one for that, but “Hear the Wind Sing” is actually my favorite for the opposite reason. Over and over, it comes up to the edge where we know what to expect, then wanders off on its own path. With Bukowski, the best parts have an extreme outsider perspective that I find oddly comforting and reassuring. He works hard in his way, and finds happiness in unlikely places.

What do you think are your greatest strengths as an instructor?

What do you think are your greatest strengths as an instructor?

You may be able to train a dog with the standard carrot and stick approach, but I think people don’t really work like that. When I succeed, if I succeed, it is by showing enough of the interesting bits of a subject that people want to learn more on their own. I think the recipe for love is just unbroken attention over time, and that applies to class too. I imagine the sum of human knowledge as this big pile of interesting stuff, and my role as a guide, to lead people up one of the paths I know to the top where they can get a sense of the shape of it.

Why did you choose to focus on virology?

How does anything happen? There was a lot of chance in it. I think a career is a thing that only really makes sense in retrospect, and at the time, you are just fighting through the difficulties in front of you and looking for opportunities. As a kid I liked to look at things closely, and sort them based on details – spotting fossils out of rocks, watermarks on stamps, mint errors on pennies. It feels a lot like finding treasure. At university, I was a standard biology pre-med student. I had spent a year’s exchange in the UK, and needed to join a lab for an honors capstone project. As it happens, by the time I returned, there were only two labs still accepting students. One working with a skin cream manufacturer on the effect of “hydrating” beauty products on E-cadherin, and a second working on treating a plant virus with anti-HIV drugs. I picked the second because it meant I got to spend time in the greenhouse planting turnip seeds. I did a lot of dish-washing in that lab – I liked how the test tubes looked when they were all clean and drying on pegs. When the term was over, I found I had mis-aligned my courses and ended up needing a Latin class that was not going to be offered until the following year. I talked to the plant virologist about this, and said that since I was still on scholarship, I would have time to volunteer in a lab, and he recommended one over at the medical school, a fellow who worked on coronaviruses. Working there convinced me that I might be OK in science, and since I didn’t really like people or blood all that much, it seemed like a nice alternative to med school. I’ve more or less stuck with coronaviruses since then.

Describe the course that has had the greatest impact on your thinking.

Describe the course that has had the greatest impact on your thinking.

I had a seminar-style honors English class on Gypsy, or more properly, Rom culture. It was taught by a specialist who had learned their language and lived among them – a very old-school anthropology approach. It was the first time that the idea really stuck with me that there were different cultures living all stacked up in the same place, but in worlds that only barely touched each other. I think the real lesson there was that when you see things from the other person’s point of view, whatever they are doing usually makes sense. And, if it doesn’t, you’re probably just missing some information. At the time, I think this course didn’t make a big impression, but over the years, it turned out to be really useful.

Give us 5 adjectives that describe you as a scientist.

If I have a skill as a scientist, it is being willing to sit there and pick at a problem until it unravels. Sitting still and focusing for long periods of time is an underappreciated skill, I think. Brute force experimentation also has a certain charm for me. Clever experimental design is aspirational, but there are problems that I think are best solved by picking up a bigger hammer. When the dataset runs deep, analysis is a beautiful tool for uncovering first principles and getting the gist of how stuff works.

What projects will you work on next?

What projects will you work on next?

I think taxonomy has a purpose beyond merely giving names to things that already exist. If nature works like a big random number generator, then anything that exists, whether it is a virus sequence that was captured when someone was trying to study a leafhopper, or a long-extinct fossil brachiopod, represents a winning combination of genes, ecology and a pinch of luck. In studying biology, I think we are often really studying fitness – the interplay of traits over generations. If we do it right, mapping these peaks of fitness, past and present, may help guide us safely to the future, like a ship through a storm. I couldn’t tell you what shape it will take, but I expect I’ll be following this course for a while.